Celebrating Nonna: 70 years of Cooking

the Story of a Woman and her Italian Kitchen work, from the 1940's to contemporary days.

August 18th would have been Assunta’s birthday. My grandma, named after the holiday of l’Assunzione - the day Mary ascended to heaven, worked in kitchens all her life. I dedicate this post to her loving memory.

It was 1943.

Assunta and her older brother had stranded away from their house in the countryside of Urbino. Their house, a nondescript cascina like many others, with tattered walls and small windows, sat cradled in a nook at the foot of the hills around the city. Surrounded by the woods, it hid far enough from town to be inconspicuous, but not near enough to make life easy for their mother, who’d walk four hours each day to go sell eggs.

I don’t know what made them strand away from home, in time of war, when they were specifically told not to, and she didn’t remember either. At 8 and 11 respectively, they were supposed to be at work in the fields. They maybe have been looking for wood, so they approached the forest.

That’s when they saw the rifle.

They recognized the German uniform, peeking out from the thick foliage.

This is what deer must feel like, she thought. You’re walking around your home and, one day, you see a guy poking out of the bushes, pointing a rifle at you. You only have about a split second to realize your life is over, and you’ll have time to realize nothing else.

The shot wasn’t coming. The brothers instinctively held each other.

The German dropped his rifle, raised his hands. He pulled a thing out of his pocket.

He approached them, smiling. He gestured as if to tell them not to be afraid.

He presented them the thing he had pulled out. It was a photo, depicting two kids. He pointed at them, then patted his other hand on his heart. See? These are my kids, he wanted to say. They’re just like you. I miss them.

Then, urgently, he directed them towards their house. He told them to never stray away from home again, that it was very dangerous. They couldn’t understand German, but he sounded like any parent scolding their kids. He saw them on their way and, when Assunta turned, she saw him dive back into the bushes, a tiny dot in the distance.

How do you live a life knowing you’re the deer and not the hunter?

By retaining one of two notions: that enough mercy in this world existed to let you go, or that enough cruelty in this world exists that no matter how many times you’re spared, someone will always be lurking amongst the bushes.

Assunta had always lived by the first, though she knew many a young boy who never came back from amidst those woods. Throughout her life, she kept wondering if that soldier ever saw the kids in the photo again, if he made it back. Makes you wonder who’s the hunter or the hunted, she’d say.

Many times, I thought she did not have the literal education to know how to be evil. Maybe it was due to the meekness women were taught to have back then, but the truth is that, in the cruel world of war and poverty she was born in, she was the kind of person who grew up thinking someone with a rifle wouldn’t actually shoot, though death and killing occurred daily in an Italian farm, where she lived and worked. They learned to kill hens as kids, before passing onto larger animals. It was the family business and their only access to food.

It was probably her sweet nature and her constant smiling that made Ottavio fall in love with her. In a world in which her own dad had chosen his wife because she was said to be the best tagliatelle-maker in town, falling for a girl’s smile was the epitome of romanticism.

He was employed as a hand in her dad’s farm when he was nine, and saw her flourish into a young lady. When he approached her she was uncertain, as she was just 16 and he was already 22. So he waited.

One day, when she was just eighteen, she got a bad bronchitis. They’d all often sleep in the cold, waking up to the water droplets from their breath frozen on the bedsheets under their nose. Somehow, the family believed that a good way to cure colds was to drink from the buckets where the cows drank. Ottavio did not really believe the bullcrap, but for a moment there they were afraid she wouldn’t make it. Each family had its beliefs and rituals. After all, his own sisters were convinced that smearing pigeon crap on their chests would make their breasts grow bigger (true story).

Her dad prayed, kneeling down, arms open before the Cross. When you have barely nothing to cling to, every grain of sand becomes a rock.

So he took the bucket, and scrubbed it as clean as he could (possibly dispelling the very reason why someone would have to drink from the bucket, but then again, what bullshit was that?). He rinsed it well, and put water in it for her to drink. He waked with her in the stable with the cows, the warmest place in any farmhouse.

And he waited.

She got better. And she realized that she could not ask for a better man if she prayed to all the gods she could name.

When they married, work in the countryside started to subside. They moved to town, Ottavio started working as a builder and she started working in kitchens, in heavy duty canteens.

She told me how she’d take the regionale train to Bologna - a full 2 hours ride, to cook for events at the fiera, in an equipe that made pasta by hand for thousands of people. She worked for a chef who she remembered as ‘a very good cook who made exceptional, crispy pizza in teglia, and I wanted to see how he made it.’

Both her and, as soon as she was fourteen, my mother, started working the stagioni.

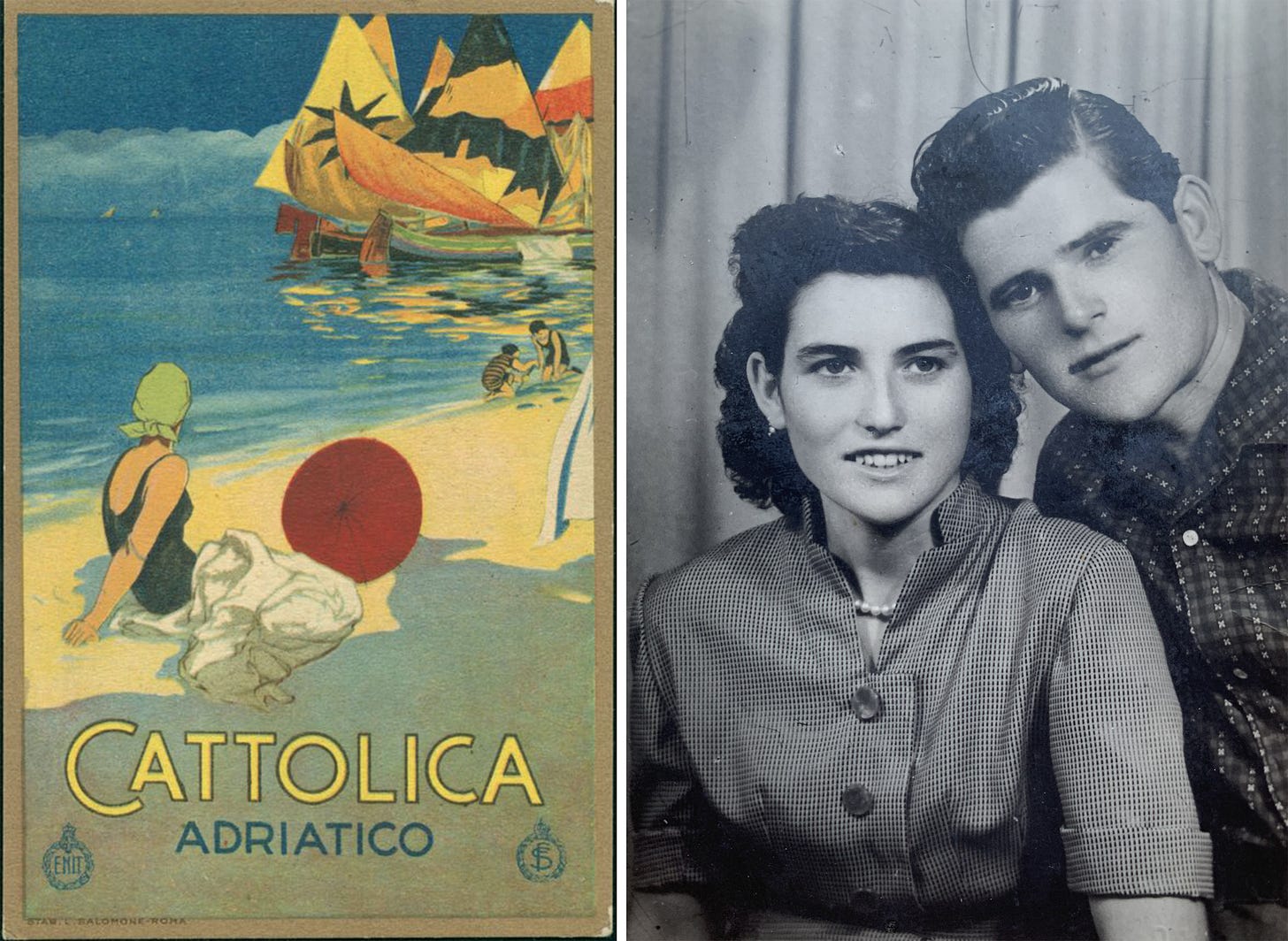

La stagione, in our Riviera Romagnola - the strip of land blessed by the sea between Romagna and Marche, was the roughly 5 month-long period in which hotels reopened, restaurants took tables outside, Germans came swarming through our streets. The towns on the riviera craved life and drank that summer high in bucketfuls, thirsty from a still winter. Most of the locals worked either at sea or in kitchens.

For a time, nonna and mamma worked at the canteens of the ex-fascist colonies that were still used to host kids on their summer vacation. Le Navi were large, supposedly ship-shaped concrete buildings, the doors painted deep blue to try and assuage their almost inappropriate appearance next to the shining sea, like a last-minute invitee who hastily wore too large, too dirty a jacket for a party. These lazy wrecks, beached on our shores from the past fascist regime, still hosted thousands of kids, parked there by tired parents coming from the north.

Five people worked in the kitchens of those ugly buildings, maneuvering pots the size of oil tanks, making lunch for one thousand kids every day. Le Navi still exist today, still an unmatched eyesore together with their neighboring sidekicks, a 1970s four-star hotel and - only note of color - a fairy light-strung, red and white kiosk selling piadina.

‘The five of us could manage it,’ she said. ‘We served no gourmet meals. One took care of the pasta, one of the pasta sauce, one of the meat, one of the vegetables, the last one cut up fruit. It was no rocket science.’

Eventually, she moved to the pensioni. The pensioni are, or rather were, tiny, unpretentious hotels which, along with their modest lodgings, included meals in the price. Usually two or three people could run the kitchen, lunch and dinner service, with a brief pause in between where the workers would just pass out on their beds, hardly even removing their aprons.

When seasons got too demanding for life with three small children, she went a servizio. She did what her husband’s sister had done: become a servant in rich peoples’ houses.

She was hired to do the cooking and cleaning at the house of one Jewish lady, who owned a luxury fabric store downstairs, in the nicest area of the town center. The store still exists and the lady is still alive and well.

‘Tell her whose niece you are,’ said my mom when I told her I was going to her store. ‘She’ll be glad to know.’

The lady from the shop uttered an oooooh! And clapped her hands.

‘Tell her I say hi,’ she said. ‘She was so sweet. We all loved her. She cooked so well. She truly made us feel at home.’

Assunta then told me stories of how she went to the market to select fresh seafood everyday. Huge platters of boiled crustaceans dressed with fresh herbs and olive oil, cod with a hint of herbed mayo, tiny soles from the Adriatic cooked in a light tomato sauce. Mussels alla Tarantina, clams in thick garlic broth. Availability of fish ebbed and flowed like the very tide of the seas, but she could cook the entire Adriatic. Cleaning seafood takes the highest toll on your hands, torturing them with cuts from hard shells, bones, spiky gills. As if for revenge for the little-to-no pity reserved for creatures of the sea, which are not spared from cruelty. Canocchie, better known as squilla mantis, one of the Adriatic’s specialties though probably only available along our coasts, must be purchased alive. Because the flesh never detaches from the shell, I was taught that the best thing to do is to put them in the fridge on their backs, and let them die slowly upside down, like hanged men. For some reason, this helps the flesh come loose easily. Throughout my life, I have seen countless bowls filled with plastic bags full of live canocchie being shoved in my grandma’s fridge, their tiny legs moving inside.

How do you live a life knowing you’re the hunter and not the deer? Often, by not realizing, or caring, that you’re the hunter. There is a sort of lingering threshold, loosely within eye reach and yet distant, that the mindless hunter will not surpass. Because the moment they do, they’re either disgusted by the trophies they collected, or become thirsty for more.

But, even in the wake of conscience, no hunter ever lets go of their rifle, as all hunters know other hunters way better than any game.

With all the animals they finally had access to, with all the animals they could finally kill to eat for themselves after the poverty of the war, Assunta never thought for one moment that, for once in her life, she could be the huntress. Yet she was, in a sort of caveman-like fashion, as someone who could finally reclaim her right to have her and - most importantly - her children’s belly filled.

She and her sisters sat in a circle around a huge cauldron, boiling off a gas stove attached to a large tank on the concrete floor in the back of the house, handling lifeless fat hens, feathers everywhere, as they idly chatted about relatives and their whereabouts, who married who, hot stuff in the neighbourhood.

That crime scene, that blood stained garage was just the last, Ill-concealed belch through which they expelled the last stale air of poverty left in their stomachs.

But poverty, in a fast-paced, ever hungrier world, is trauma that manifests in ways like buying nice things and leaving them untouched, or saving the best for a rainy day with the likely result of never using it.

The killing of the animals, and the celebration of their animals’ sacrifice, was the only time they’d live in the present, enjoy the feast.

They used that same cauldron for all the key moments of the year: making tomato passata in the summer, plucking and cleaning the guts of the hens and all game birds - pheasant, guinea fowl, mockingbirds - in the fall, washing the intestines and skin of the pigs in the winter and making insane amounts of jam in late spring.

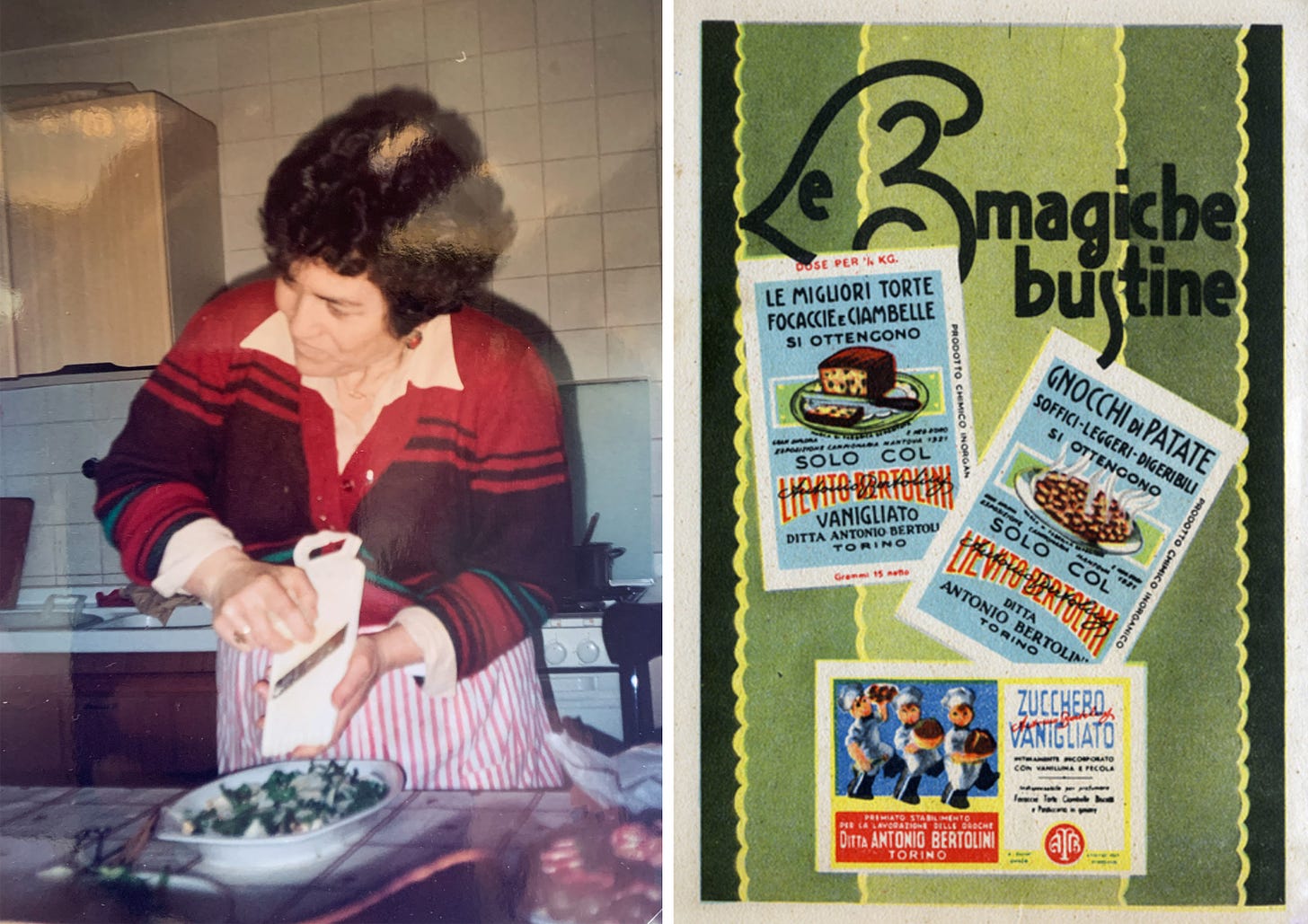

Cruel as it all might seem, I consider the witnessing of her cooking life one of the greatest blessings of my existence. I can cook because I saw her and mom in the kitchen, all their life, at home and at work. My childhood summers were my grandma and mom clad in white aprons and caps, sweaty in their kitchen clogs, cleaning pots so big I could have easily fit into them. They weren’t just home cooks: they were single handedly responsible for the meals for hundreds of tourists.

She spent a life making people feel at home through her cooking. My memories of her are with her aprons always on, standing on the stove while the people already sat eating. The memories are especially vivid around holidays, and especially Easter, where they’d cook up a seasonal feast: like that one scene in My Big Fat Greek Wedding, they would order a lamb, then chop it, braise it, grill it, stew it. Only one time per year, she would make what she called alberini, bone-in lamb ribs, breaded and deep fried. It all came with braised herbs in lots of garlic and olive oil, and pomodori al gratin - very similar to tomates provençales, oven-baked tomatoes topped with oily, garlicky breadcrumbs. Then grilled zucchini with a bit of ricotta smeared on them, rolled up, and served with minced mint, pine nuts, a drizzle of olive oil.

Of course, there would be Asparagus tagliatelle, swimming in a pool of fat, topped with Parmigiano like snow on a hill.

Each sunday was a feast of homemade pastas, gnocchi, roasts, hours spent cleaning and prepping vegetables coming straight from her brothers’ gardens. Grandma, mom and her aunt started the works early in the morning with handmade pasta, then moving on to the vegetables. The kids would hide under the table and snatch a raw gnocco or a raw strozzaprete to eat, until they’d scold us away.

The Photo I wanted to use for the head of this article was one of Assunta taking roast tomatoes al gratè out of the oven, but I can’t find it anymore. It had always been sitting in a drawer in my mother’s house, and it must have gotten lost in the move. It is one of the most iconic memories I have of her - her taking out food from the oven on a sunday morning.

Today, I feel guilty if I see people standing and trafficking while I sit down and eat. It is only now that I am a grown woman that I understand the duality of this behavior, of the women who had to take care of everyone else first. She wouldn’t have cared about the feminist discourse. She was, in her hurting legs and tattered clogs, happy to see the family fed. Women like her never though they could possibly have another purpose in life and, even if she did, she would not care.

She left like all practical people do: with the knowledge that she clung around as long as she was needed, and went serenely once she knew she wasn’t anymore. A sort of Irish goodbye, a feeling akin to the one I felt when I saw her finally sitting down at the table, collecting the scraps of what was left on the pans on her plate, her apron kept on.

Her husband and her son passed before her. It’s the men who need tending to. Her two daughters did perfectly fine without mom. She could go.

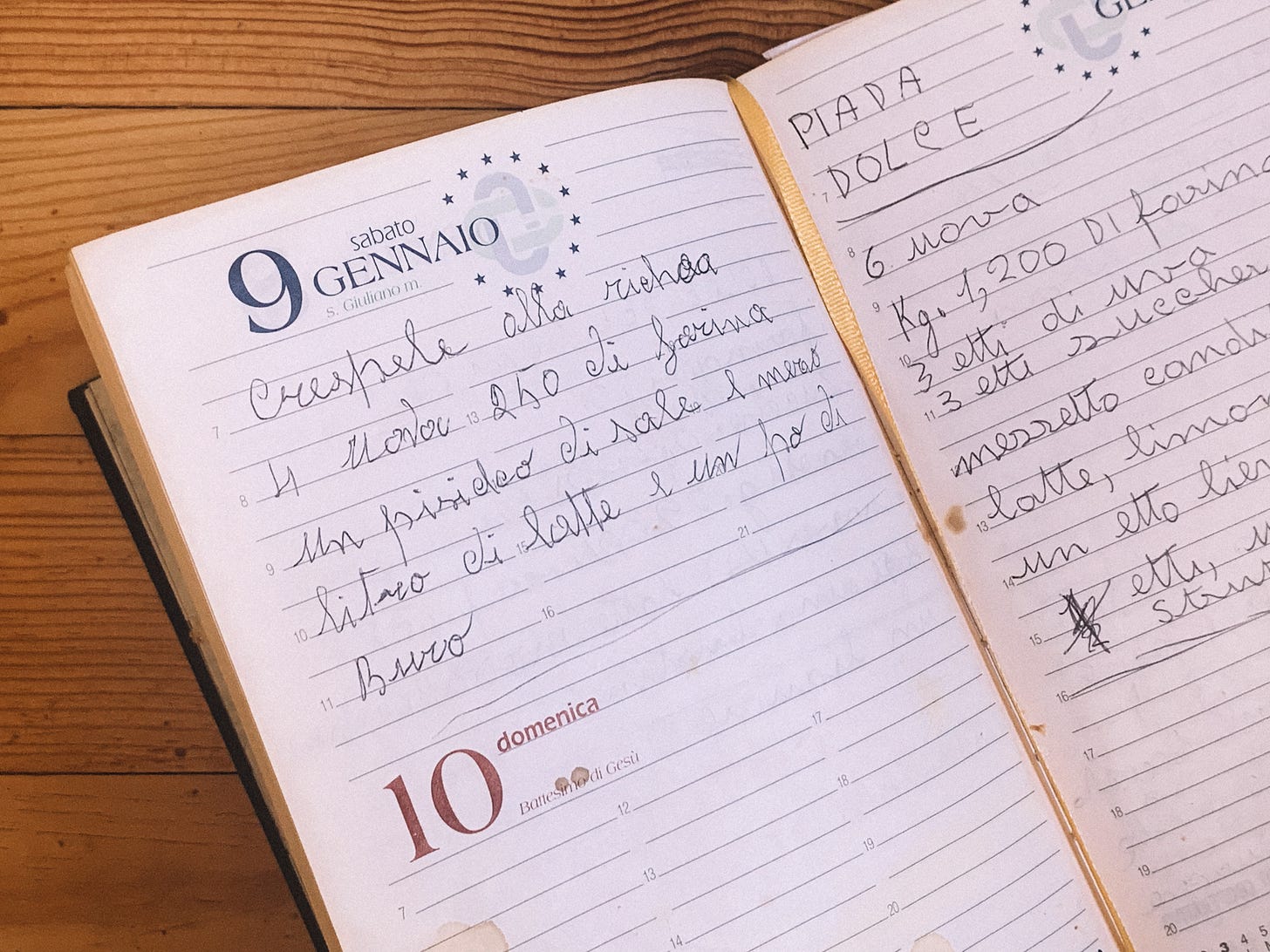

She left much behind her. Amongst the practicalities, several shirts she had sewn herself and her notebook. The shirts were made with the luxury fabrics the Jewish lady gifted her.

Her notebook was continued by my mom. I jotted down some of her recipes in it too.

The agenda was one of those leather-bound gadgets the bank sent as a gift, dated 1997. In it, she noted some basic recipes, maybe some that her friends have given her. Her trembling, child-like calligraphy was full of grammar mistakes, like her shopping lists. Sometimes I’d find some abandoned shopping list on the concrete outside the store: all bore some usual mistakes, all bore the reminder that her generation did not go to school and writing lists was the only benefit an education could bring.

The recipe for savory crepes recites ‘crespele alla richa’, when it is, in fact, ‘crespelle alla ricca’.

I wish I had recorded more of her stories, and I wish she could go without so much of what’s dear to her fall behind. Sometimes, I felt like she was carrying her life in her arms, like when you’re at a supermarket and think you don’t need a cart, and you end up struggling to hold everything, tomatoes and packets escaping left and right, apples falling and getting bruised.

But there’s always going to be something left behind, something escaped. There’s always gonna be some kind of remorse about things you could have done better, things you could have snatched from life that, finally, you couldn’t.

Every thing we managed to snatch from life we snatched for you, she’d tell us. No suffering is in vain. For every bit of suffering, we squeezed out some more life to give you.

Surely, as Ottavio said, somehow you’ll have to die. But, somehow, you’ll have to live, too.

How do you live knowing you’re the hunted, turned the hunter?

‘It’s your life,’ she’d say. ‘Run for it until you’re faster than the bullets.’

I've been following your writing for over eight years and this is one of my all time favorite pieces you've published. I love your recipes, but the way you write about life, family and culture really resonates. Please tell me there's another book in the works!

Thank you so much for this lovely piece of writing- and yes, now I’m very hungry and also very inspired