Angels in Heaven Eat Nothing but White Flour

A Story of Pasta Antifascista through the eyes of my Nonno.

This article was inspired by the beautiful article published by about the story of pasta in bianco, which you should absolutely read here.

Recipe at the bottom. Though this isn’t really about the recipe.

When all the health food craze started to pour over from the US into Europe - 2014 circa, I brought a loaf of very dark bread home at my grandparents’.

My Grandpa, sitting on the step of the fireplace, smoking a cigarette in his white tank as he usually did, rose an eyebrow from behind a rogue lock in his otherwise perfect coiffure.

“What’s that you have there?” he barked.

“Whole wheat bread”

“And why would you buy that?”

“It’s better for you than white flour, isnt’it?”

He sighed, threw the butt of his cigarette into the fireplace, and rose.

“Can’t believe it,” he sighed. “We dreamed of feeding that to the chickens when we were young, and now you buy it willingly?”

And off he went.

I needed my mom to later explain his reaction to me, as I would have never thought that a loaf of bread could be the cause of raised eyebrows.

“That’s post-war life,” she said. “Food was rationed when they were kids. White bread was a thing of nobility - they sure couldn’t afford white flour. That came much later. Bread was only made with all the scraps of dark flours they could find. White flour is probably one of the greatest post-war luxuries they could embrace in their everyday life.”

“They have to thank Omero for their food back then”, mamma explained.

“He had signed up to the Fascist party, and he was a man of high status. He could sneak in a few extra food tickets. I don’t think my dad ever liked it much.”

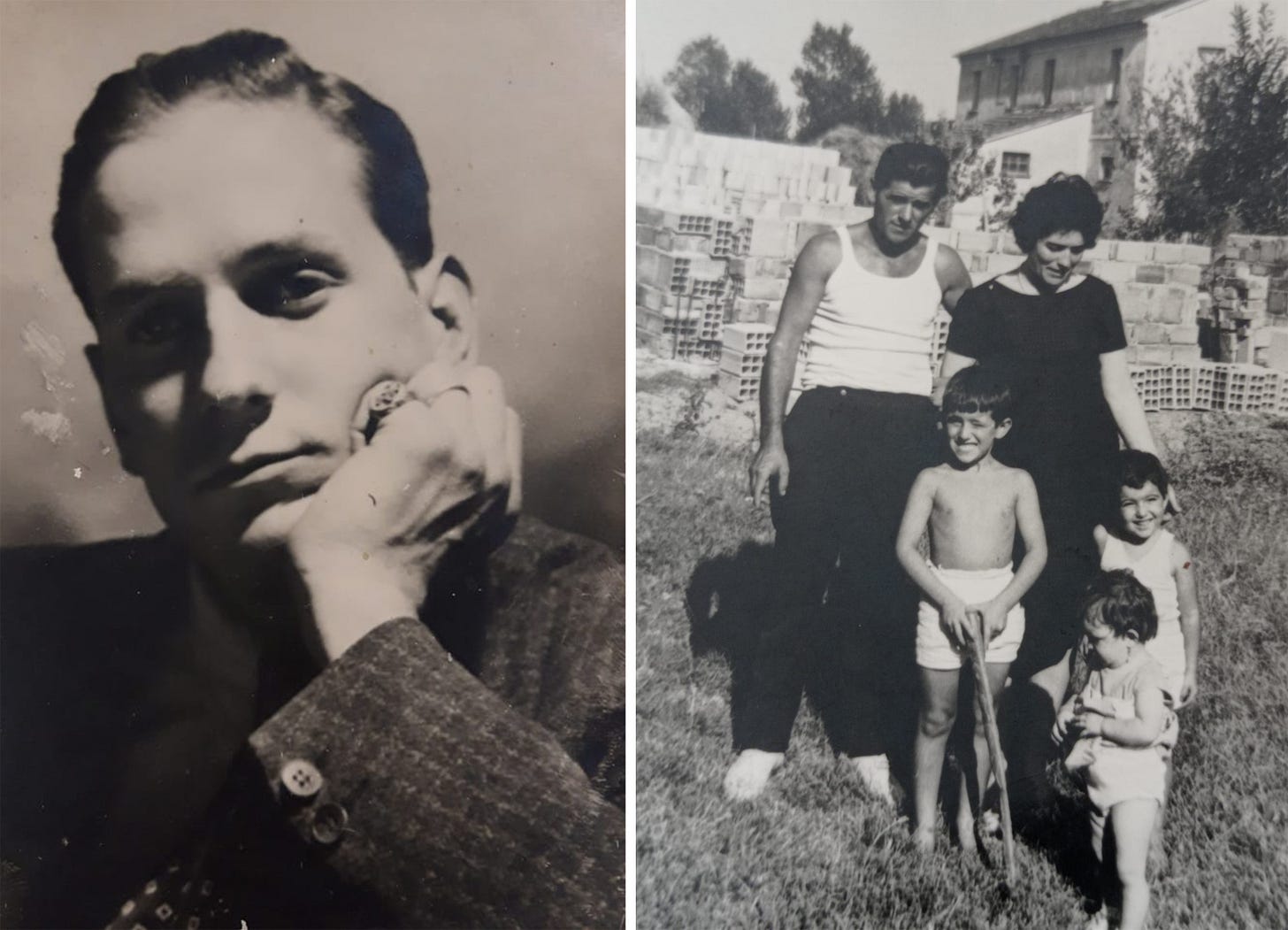

Second-to-last of a brood of nine kids, born in 1928, my grandpa was called Ottavio (which means ‘the eight’, in the lack of creativity that characterised countryside parents with many children at the time). He started working in the fields as soon as he could walk, started smoking at 9 and, around the same age, decided he’d always be clean, well dressed and well coiffed even though he was a peasant. His wave of hair, which he pulled back with a slick of brilliantina every day after work, is one of the most iconic pictures we all as a family have lovingly hung in the gallery of our memories.

His oldest sister, Dosolina, made it clear from a very young age that she wouldn’t put up with the countryside business, and that she would have much preferred cleaning the shitters of some rich family in the city. So to the city she went, and she ended up cleaning the shitters of one of the most handsome, most well-to-do men in Urbino, Omero, who fell in love with her. She was very beautiful and, even in her maid outfit, had the flair of a television actress. He bore the name of a Greek poet - Homer - wore nice hats, gloves, jewelry, tailored coats. He was a photographer and an antiques dealer. He asked for her hand in marriage. Not that he was the kind of man who needed to ask.

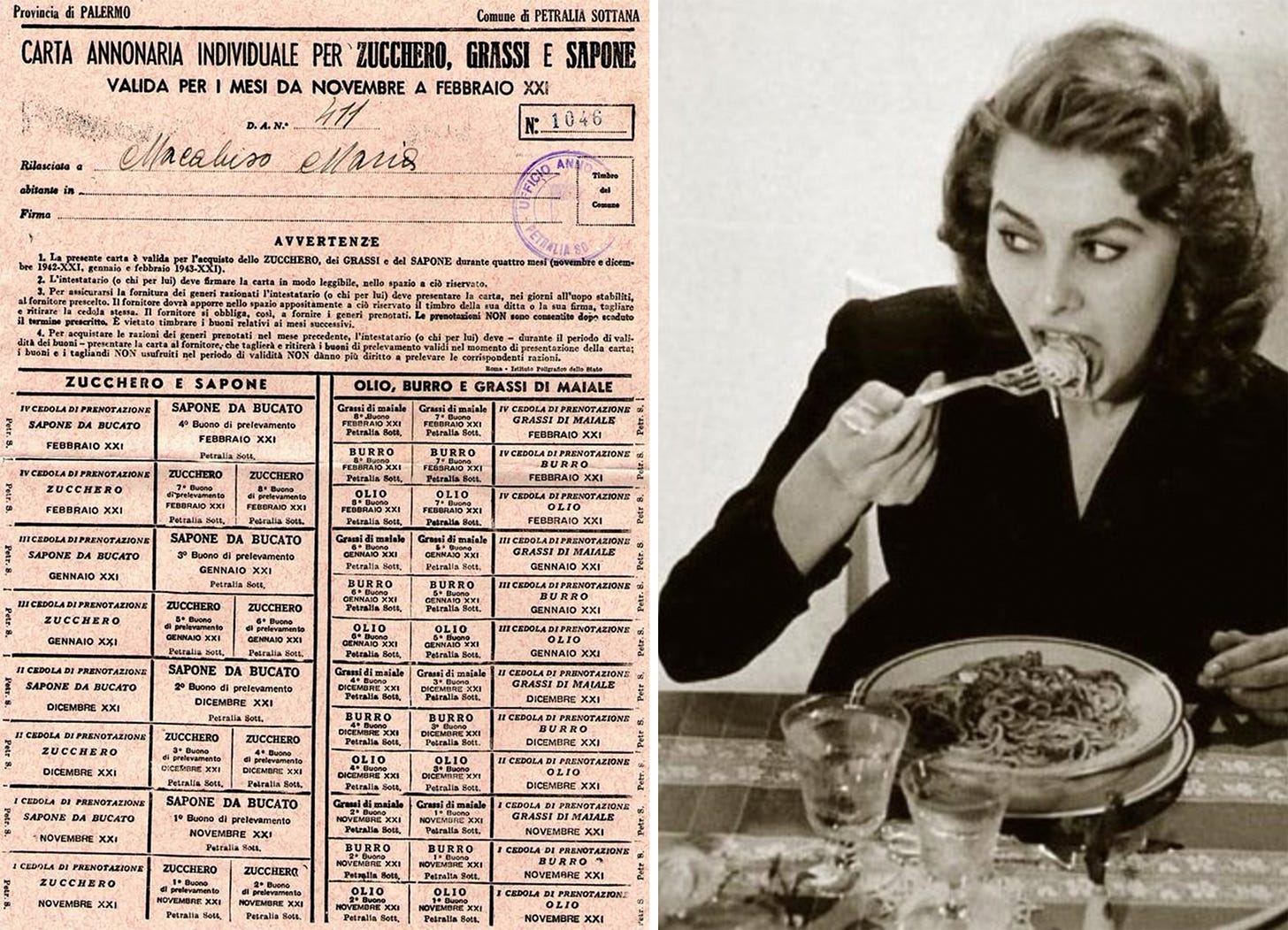

Omero, as a man of status, had the tessera (card) of the Fascist Party, with all the benefits it entailed.

When Mussolini put into effect the leggi fascistissime (‘very fascist laws’) the country turned into a dictatorship. All freedom of speech, creation of other political parties or cultural associations, reunions, rights to go into strike, and many other things were abolished. Signing up to the fascist party gave families the right to a tessera annonaria and, therefore, to food.

The tessera was a card with stamps, which gave families the right to some small amounts of food every day. Basic ingredients were heavily rationed. Those living in the countryside could maybe sneak some extra vegetables into their plates, or the occasional chicken, provided that their landlord - or worse, some German soldiers passing by, wouldn’t take the food away before they could eat it. I’m told that, one time, soldiers came at the door and my mother’s grandfather stepped in. They pointed a rifle at his chest, demanding he gave them his last chicken.

“You might as well kill us all,” he told them, his chest straight. “This chicken is the last food I have left for my family.”

The soldier lowered the rifle, accepted some bread, and off they went. That miraculous story is still a bit of a legend within the family.

Everyone says that Omero didn’t care much for the politics; he just wanted to keep his status and make sure that everyone was fed at least a slice of bread. It sounded like the practical thing to do.

And still I imagine what that could have meant to my grandpa Ottavio - a man who, in his boyhood, would grow to become a militant antifascist, red-handkerchief-at-the-neck, raised fist kind of guy - as he had to shut up and lower his head, well aware that neither pride nor ideals would have kept the family alive.

The family never signed up to the fascist party. I like to think that, other than giving them food, Omero effectively gave them the freedom to stick to their ideals.

Ottavio wasn’t old enough to go to war. But his older brother was.

He never came back. He was one of the dispersi in Friuli, in the mountains at the border with Slovenia, their bodies forever lost to the frost of winter. His picture still hangs somewhere in the house.

Before leaving, he had bought a ring for his fiancee, planning to marry her after his return. She gave back the ring to the family - a simple silver thing with a tiny river pearl. My mother still keeps it.

The war was over by the time he turned 18, and Ottavio never did the mandatory 2 years in the military. He had suffered from a strong otitis as a young boy, which left him half deaf from an ear, making him unsuitable to become a soldier. In a time where men purposefully cut off a finger or tried to break their own legs to avoid going to the military, this was received as the highest of blessings.

Before and during the war they’d mostly eat polenta, which was poured on a large wooden board and cut with a metal wire. Sometimes they’d stick a single piece of meat in the middle of it, or an herring, where everyone could rub their piece of bread to give it some flavor.

Because food was so scarce, especially around 1935, the cultural movement at the time, the Movimento Futurista, which started in 1909 and survived well into the thirties, preached a diet that was apt for ‘the modern man’ who was expected to behave like a soldier, based on frugal meals that could temper the body and prevent vice and useless pleasures. While they hid it under the vessel of machism, it was no more than a poor gimmick to try and hide the fact that there simply was not enough food. In Italian, we’d call this a paraculata.

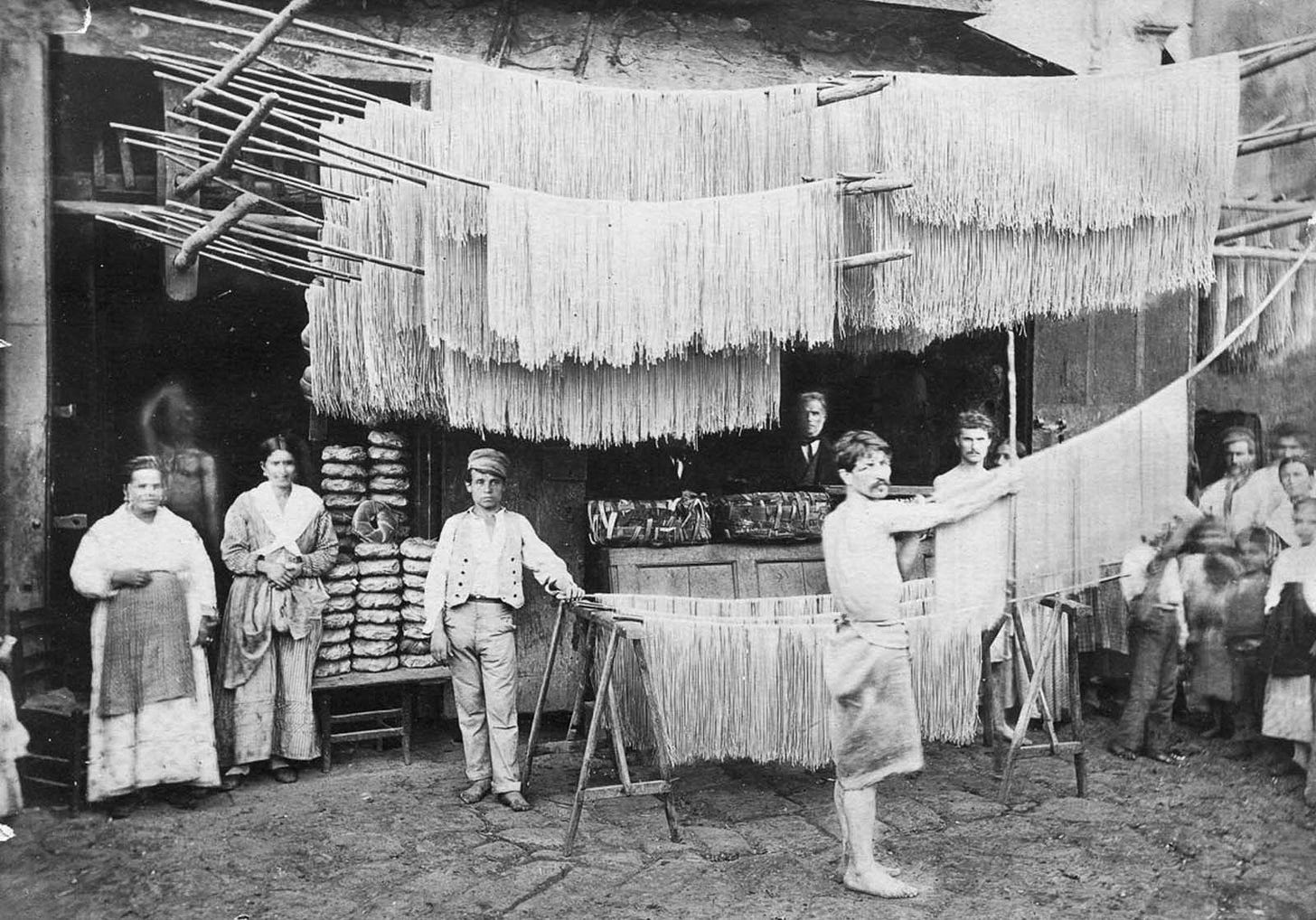

Pastasciutta in particular, in the vision of Marinetti, who published the Manifesto della Cucina Futurista, was a food that contributed to slouchiness and unnecessary indulgence. Furthermore, Italy never managed to produce enough wheat to keep up with the demand. Fascists, who hated everything that was not purely Italian, did not want to import wheat from somewhere, so their manifesto encouraged people to eat rice instead.

The battle against pasta eventually became so fired up that people took to the streets.

In her article, Emiko Davies mentions an answer given by the Mayor of Naples to the Futuristi who wanted to eliminate pasta: “The angels in heaven eat nothing but vermicelli al pomodoro.”

My grandpa and many others would have said that angels in heaven eat at the very least nothing but white flour.

What is paradise, if not a place where you don’t have to use pig food - as barley and oat was - to make your own bread?

When the Duca Bonvino, Mayor of Naples, and Marinetti were exchanging fire letters about whether or not pasta would be the life saver or the damnation of Italians, Ottavio wasn’t in this world yet. And neither was pasta in the north of Italy. Incredible as it may sound, pastasciutta (the term that described durum wheat pasta left to dry until hard, that we all find in supermarkets today) was really a thing of southern Italy, especially Naples. It was only after the war that pasta gained its place at every Italian’s table, pretty much eaten for every single lunch. My mom’s nonna would make pasta Fresca - tagliatelle, tagliolini and the like, sometimes without eggs if there weren’t any, and would dress them with la bomba, a few dice of tomato stir fried in pork fat and rosemary. But pastasciutta was still nowhere to be seen.

Ottavio was definitely around in July 25th 1943, when Mussolini was overturned and arrested.

This is where the pasta in Bianco truly rose to its fame. A family from the countryside of Reggio Emilia, the famiglia Cervi, made pasta in bianco - some 370 kilos of it - for everyone to eat. They milled their own flour; it was harvest time and they had plenty, and made pasta with their own bronze extruders.

The area of Reggio Emilia was a huge center of Partigiani, the antifascists. The staffette, usually young girls, were responsible for carrying hidden messages, food and other items between families, as gatherings were strictly forbidden. Anna del Conte tells about it in her beautiful memoir Risotto with Nettles, riding her bike with letters hidden in the inner seam of her skirt.

The Emilia region is, more than anything, famous for butter and cheese, being the birthplace of Parmigiano. That is what they dressed the pasta with: butter and cheese. The epitome of luxury. I think that my whole family at the time never even saw a block of butter. Sure, they had cows, but all the milk had to go towards the making of the cheese, as pork fat was enough to satisfy their cooking needs.

But pastasciutta? Never.

As they ate their first real bowl of pasta, they knew they were eating their freedom. They ate the end of the war. They ate the end of famine, restriction and dictatorship. They ate the first glimpse of some hope for their future.

What could better end something Italian made like Fascism, if not the opposite spectrum of the made in Italy? Death by pasta in Bianco. That works.

Angels in heaven must indeed eat nothing but white flour.

I realize now that, for Ottavio, eating bread made with grains destined to pigs and accepting the food tickets from Omero were nightmares weaved of the same thread. We ate the flour we’d use for the damn pigs, he’d say.

Why would you?

Ottavio, and many other Italians like him, went on to have pasta every day for lunch for the rest of their life.

I think that skipping his military duty at the time somehow spared him the trauma that caused such dryness of spirit in so many others. When the economy picked up, and the caporalato (landlords exploiting farmers to work on their land in exchange of some food) ended, he left the field work and went on to become a builder. He was stern, but kind. He had authority, but was not imposing.

One time, after I had eaten a bowl of pasta in Bianco, I wanted to change my plate as there was quite a bit of floating fat left at the bottom.

‘what’s wrong with your plate?’ He growled. “You’re not the one doing the dishes in this house. Keep the plate and clean up after you’re done. We’re not your servants.”

I was 8. I never changed a plate or left one in the sink since then.

We’re not your servants. And it was true.

They were nobody’s servants. Not anymore.

Ottavio was, unlike many others, a man who did the dishes and helped my grandma clean up all the time. At the time, this was unheard of amongst Italian men.

”He was such a good house man,” my grandma said all the time. “And he never looked at other women”.

Maybe proof of that was that he’d take me to the bar with him.

The bar was a big, smoky place flooded with the green light of the billiards tables, where crowds of men in nice pants and shirts downed amari and Marlboro as they played cards, screaming and swearing. It wasn’t really a place for children.

It was their place, every night. I realise now that, much as some wives complained that their husbands were at the bar one too many night, it was the place they carved out and deserved as their god forsaken right after years of being hungry, tired and scared. I loved to watch him destroy the other nonni at cards. Just once I could beat him. It took me years to realise that, that night, he just let me win.

He was never fussy with his food. Much as grandma would cook up a feast on weekends, very often our meal was that very simple pasta in bianco, sometimes with a base of olive oil, sometimes with a base of butter. The same pasta in Bianco that set them free.

Many nonni had that in their rotation. When they did, they’d put the hot pasta in a bowl, add a good chunk of butter, and stirred to make it melt. Then they’d add a snowing of Parmigiano, which would stick to the pasta.

Ottavio would eat it with gusto. Can you ever really forget the first gift you were ever given in life? To him and many others, pasta in bianco was the gift of a legacy with no more oppression, handed over to everyone by the Cervi brothers.

Ottavio ate white bread and pasta and voted Partito Comunista till the very last day of his life, which came on a foggy day in November, 2017, as he approached his 90th year of age.

As we drove back from the funeral home, in the dark winter highway, my mom said:

Losing a parent really is a unique form of loneliness. You realise how much of someone’s children you are, even when you’re older, even when you’re a parent yourself. It’s still the loneliness of a child losing their parent.

I couldn’t see her eyes in the darkness, but I could hear from her voice that she had teared up. We cried in the car in silence. It was the first beloved relative I lost.

For at least a couple of years I walked into the house and sometimes I’d forget he wasn’t gonna be there. Like I could enter the living room and smell his cigarettes, see his back in his white tank. One afternoon, a few months after his death, I had entered the house and somehow completely deluded myself that he was still there. I was sure I heard his voice. I realized and I cried.

But time eases all wounds, and, for better or for worse, makes us forget.

May this pasta forever carry the unforgettable meaning it did for my grandfather.

PASTA BURRO E PARMIGIANO (PASTA IN BIANCO)

Here I’m offering two alternatives: the super simple and quick way that nonna used to make it, and a slightly more elaborate way that yields a super creamy pasta. Up to you to decide which one you prefer. Great for any pasta format.

Serves 2.

160 to 180g pasta depending on your appetite (cooking water reserved)

50g butter (better unsalted)

1 cup grated Parmigiano, or Grana

Salt for the pasta water, pepper.

Bring a pot of salted water to a boil. For reference, you can add about a tablespoon coarse salt per liter of water. For this recipe, it can be a scant tablespoon, as you will be adding some flavorful cheese.

Once the pasta boils, add the pasta and cook according to package instructions, preferably al dente. Taste the pasta for doneness, but ideally you can drain it a minute before the cooking time is over. Reserve a glass of pasta water!

Now, you can proceed two ways:METHOD 1 - NONNA’S WAY: After draining the pasta, add it to a bowl and add the butter, cut or broken in smaller chunks. Stir until melted. Add the cheese and, if you want, a tablespoon of pasta water to make it a little more creamy. Serve as is with some pepper if you like.

METHOD 2 - CACIO E PEPE WAY: this is a more *chic* way of doing it, almost a cacio e pepe. If you choose this method, you might decide to add less salt to the pasta water.

When the pasta is almost done, add the butter to a pan, and melt it until bubbling. You can even slightly brown it. When the pasta is 2 minutes from being ready, drain it and add it to the pan, reserving the pasta water. Add the cheese and 3-5 tablespoons of pasta water and stir well to make a nice cream. Serve immediately with freshly cracked pepper. I’m not a fan of pepper, but I do love wild peppers that have more of a citrusy flavor.

To the memory of Ottavio Tagliabracci, the best nonno there ever was.

Thanks zia Ester for preserving all the beautiful pictures Omero took of the family. And thanks Omero for taking so many pictures of our poor but beautiful family throughout the years.

Dear Valentina, this was a feast for my soul. My great-grandfather was technically born in Italy, although a Slovenian (the region your grandfathers brother went missing) in the 1920s. He was active in the war, joining the communist partigani (Yugoslav, not Italian), captured and imprisoned in Gonars from which he fled (a story turned legend in our family). My great-grandmother on the other hand was born in what is now a small town on the border with Austria. She has also, as a young girl barely in her teens, helped the partisans, hiding and delivering the letters.

Italian food has a special place in my heart. The Italian tradition of using cheese and eggs in everything is the only thing keeping me from turning vegan, although I am vegetarian now for almost half of my life. I think we ate extra Italian, even by Slovenian standards, because of my great-grandfather, a man who, according to my family, was of great authority, although the war years plagued him until his (what I would call surprisingly) calm death in his sleep in the nineties.

It is fascinating how much emotions, and with that power, the food holds. And when I think of it, I always remember the tradition of breaking bread with someone, usually the guest. What a powerful gesture it used to be before the abundance we now have (at least in the global west).

I could go on so many topics you opened in this essay, but I would just like to thank you, for sharing the history of your family. There is still so much hate for the reality like joining the fascist party only to survive or to remain unseen. People unfortunately forgot about the nuances of survival in the wartime.

Thank you for sharing this story about your family.